Home > Information > News

#News ·2025-01-07

The 38-year old journal used AI to alter the paper and forced all the editors away!

Recently, the "wave of departures" that shook the academic world attracted a large wave of attention: all but one of the editors of Elsevier's top journal, the Journal of Human Evolution (JHE), resigned.

What is infuriating is that the publishing giant secretly uses AI to process papers, completely fails to inform authors and editors, and even modifies content that has already been approved.

Not only that, papers submitted by famous scientists have also been arbitrarily changed by AI.

The reason behind this is that the cost of labor is too high, and publishers want to further cut costs through AI.

John Hawks, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was stunned to find that four of his 17 most recent JHE papers had been processed by AI without receiving any notification.

"If I had known that AI might change the meaning of the article, I would have absolutely chosen to submit it elsewhere," he fumed.

Over the weekend, JHE's editorial board posted a full online resignation statement, "This is an extremely painful decision for each of us."

Address: https://retractionwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Social-Media-Statement-re-JHE-Resignations.pdf

Beginning in 2023, Elsevier quietly introduced AI into the journal production process without warning.

And the consequences of that decision are simply jaw-dropping

Not only did AI arbitrarily rewrite papers that had been reviewed by editors, but a large number of style and formatting errors emerged.

Even more intolerable is that the meaning of the paper has been changed by AI.

In its latest statement, the editorial board noted several changes that have taken place over the past decade that go against JHE's long-standing editorial principles.

This includes removing support for copy editors and special issue editors.

Elsevier also brags that "editors should not be concerned with language, grammar, readability, consistency, or accuracy of terminology and formatting."

In addition to AI altering papers, they also made a series of chilling decisions.

The most immediate consequence of plans to cut the number of deputy editors by more than half, for example, is that fewer editors will handle more work.

In addition, Elsevier's "unilateral full control" of the editorial board structure in 2023, forcing all associate editors to renew their contracts annually, while creating a symbolic third tier of editorial boards, directly compromises editorial independence and integrity.

Over the past 38 years, the editors have devoted a great deal of effort to establishing JHE as the leading journal in the field of paleoanthropology.

We have a deep affection for the journal, the discipline, and the academic community as a whole. However, in the face of the current situation, we have found that continuing to work with Elsevier has created a fundamental conflict with our academic conscience and professional ethics. This contradiction forces us to make difficult choices.

Elsevier has long been criticized, and this latest development only adds to the controversy.

Some in-house production jobs have been cut or outsourced, and AI has been secretly introduced without editors being told.

According to the editors of the Collective Uprising, "This caused great distress to the journal, and it took us six months to barely solve the problem caused by AI."

Even so, AI processing continues to be used, often reformatting submitted manuscripts, resulting in changes in content meaning and formatting that require significant oversight by authors and editors during the proofreading phase.

In addition, JHE's page costs are higher than Elsevier's other for-profit journals, and even more than the well-known comprehensive open access journal Scientific Reports.

Faced with this sky-high cost, many journal authors can not afford.

In a statement, the editors noted that "this is completely contrary to Elsevier's commitment to the principles of equality and inclusion."

The turning point seems to have peaked in November.

At the time, Elsevier informed co-editors Mark Grabowski (Liverpool John Moores University) and Andrea Taylor (California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Tulo University) that it would end the "dual editor system" in place since 1986.

When Grabowski and Taylor protested, they were told the system could only be maintained if they accepted a 50% pay cut.

PZ Myers, a biologist at the University of Minnesota at Morris, said in a blog post, "Elsevier has continued to mismanage and maximize profits at the expense of quality.

In particular, they argued that human editing costs were too high, so they tried to replace it with AI, and proposed cutting editor-in-chief pay in half.

It is worth mentioning that Elsevier charges a processing fee of $3,990 per submitted article. Clearly, they are looking to further improve the economics of their business operating model."

It is worth noting that this is the 20th mass resignation of a scientific journal since 2023.

On December 28, UW-Madison anthropologist John Hawks published a blog post saying that he was shocked that Elsevier would introduce AI into the editorial process in 2023, and that he fully supported the decision of the editorial board members.

Hawks has published a total of 17 papers in the journal.

In the past two years, he has published four articles, including one currently in print, without receiving any notice.

He said the move violated JHE's own guidelines on how to use AI.

In effect, submitting authors have a right to know how their work will be processed by AI.

Hawks said, "If I knew that AI might change the meaning of the article, I would choose to submit it in another journal."

This incident is a wake-up call: if AI is not used properly, the cost can be catastrophic.

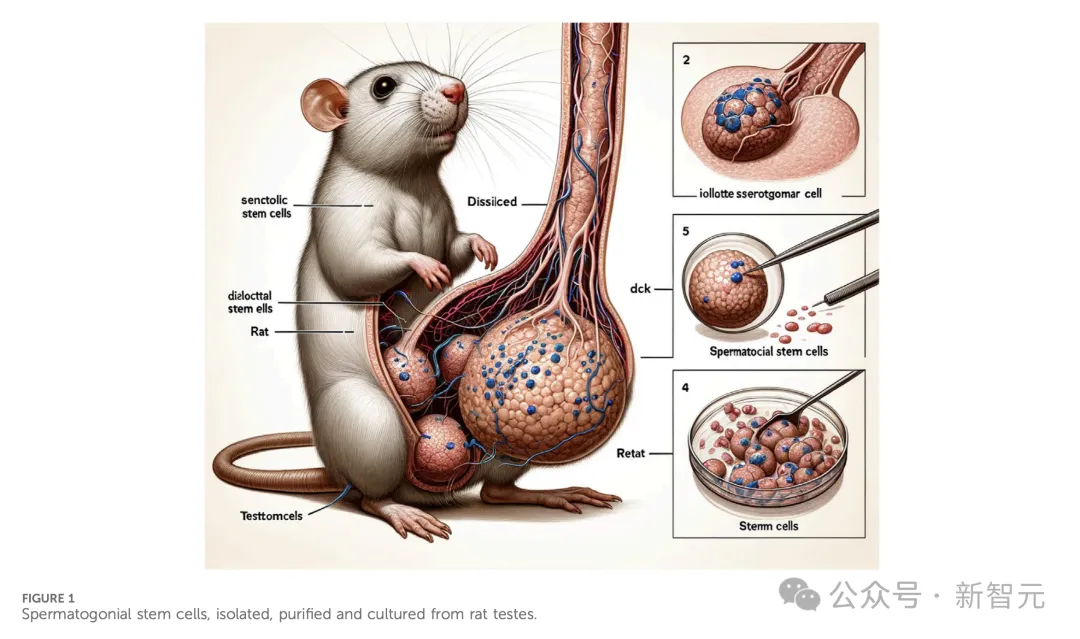

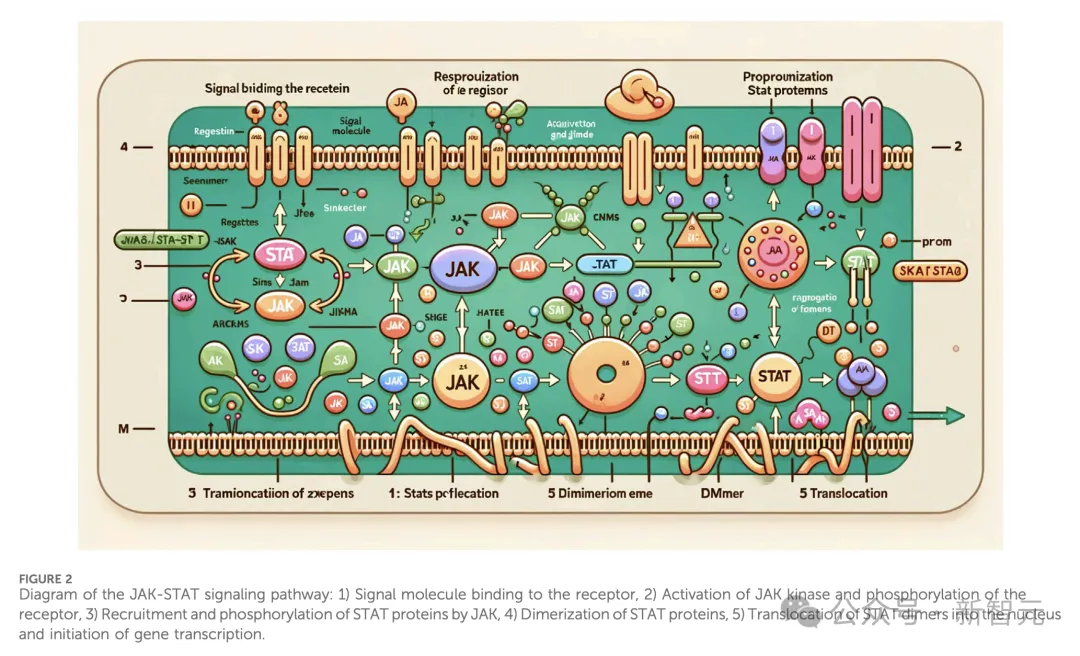

Earlier in 2024, a peer-reviewed article published in the prestigious scientific journal Frontiers featured several apparently inaccurate AI-generated images that went viral across the web.

In it, the AI generated a grotesque image of a mouse's genitals.

On social media, researchers were shocked by the images and found them ridiculous. The paper was later retracted under intense public pressure.

But it raises a deeper concern that AI, while improving productivity, could undermine the credibility of published scientific research.

However, AI also has some positive applications in scientific research.

Last January, for example, the journal Science began using AI software to automatically detect fake images.

However, such software also has limitations, and it is easy for counterfeiters who understand how the software works to avoid detection.

Hawks acknowledges in his blog that the use of AI by scientists and scientific journals may be a trend, but also recognizes its potential value.

"I don't think it will lead to a dystopian future. But the quality of machine learning applications is really uneven."

It is inappropriate for anyone to use AI to reduce or replace human scientific input and oversight in scientific research - whether that input comes from researchers, editors, reviewers, or readers.

It is unwise for a publisher to use AI to force experts to spend extra time on duplicate proofreading, or to make it more difficult to disseminate scientific results.

It is particularly galling that Elsevier requires authors to be transparent, but does not provide transparency to its own processes.

Last March, Nature published an article questioning the effectiveness of mass resignations as an emerging form of protest.

Such moves do attract attention, but they go far beyond mere protest.

Now, former Syntax editor Klaus Abels and his colleagues have set out to create an independent nonprofit journal that will maintain high academic standards while still enabling open access.

2025-02-17

2025-02-14

2025-02-13

friend link

400-000-0000

立即获取方案或咨询

top